How to buy Pacru

What & why

Pacru, Shacru

& Azacru?

News & Events

Play on computer

Contact

Home

|

|

How to buy Pacru |

What & why

|

News & Events |

Play on computer |

Contact |

Home |

|

|

|

|

|

|

WHAT & WHY: PACRU, SHACRU & AZACRU: |

||||||

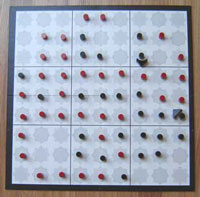

You play Pacru on a board consisting of a grid of nine squares by nine squares, divided into nine "borderlands". The game centres on the interaction between chevrons (four each) and markers. The board starts with no colour markers on the board and as the game progresses you can place markers of your own colour by moving across borders.

You play Pacru on a board consisting of a grid of nine squares by nine squares, divided into nine "borderlands". The game centres on the interaction between chevrons (four each) and markers. The board starts with no colour markers on the board and as the game progresses you can place markers of your own colour by moving across borders.

As you gain more markers in a borderland, so your chevrons there gain more power of movement. Using a connection change you can sweep a chevron across the board changing squares to your colour, or with two chevrons you can pincer an opposition chevron. You win the game by placing your 42nd marker on the board, or by eliminating all your the opponent's chevrons. You will probably take 15 minutes from first aquaintance to grasping the rules.

As you gain more markers in a borderland, so your chevrons there gain more power of movement. Using a connection change you can sweep a chevron across the board changing squares to your colour, or with two chevrons you can pincer an opposition chevron. You win the game by placing your 42nd marker on the board, or by eliminating all your the opponent's chevrons. You will probably take 15 minutes from first aquaintance to grasping the rules.

Pacru is like to appeal to players of the classic "abstract" games: Chess, Go, Othello (Reversi), Draughts (Checkers), Parcheesi as well as the more sophisticated recent games of this nature such as the GIPF series created by Kris Burm, or Sid Sackson's abstract work. Those who wish to take Pacru further can enter the Manchester Open or the Pacru Championships at the Mind Sports Olympics where Pacru sits alongside old classic games.

Pacru is like to appeal to players of the classic "abstract" games: Chess, Go, Othello (Reversi), Draughts (Checkers), Parcheesi as well as the more sophisticated recent games of this nature such as the GIPF series created by Kris Burm, or Sid Sackson's abstract work. Those who wish to take Pacru further can enter the Manchester Open or the Pacru Championships at the Mind Sports Olympics where Pacru sits alongside old classic games. Unlike many abstract games Pacru can be played by 3 or 4 players, not only two. Pacru is again unusual in having both markers (tiles, stones) and chevrons (pieces, men) and a dynamic relationship between the two. The aspect of the game where more territory in a "borderland" gives the chevrons there more power of movement can remind the player of the game Risk. The advantage of being a new strategy game is that at this point in time there is not a wealth of information on opening theory, endgame play etc. - it is that most exciting time in a game's development.

Unlike many abstract games Pacru can be played by 3 or 4 players, not only two. Pacru is again unusual in having both markers (tiles, stones) and chevrons (pieces, men) and a dynamic relationship between the two. The aspect of the game where more territory in a "borderland" gives the chevrons there more power of movement can remind the player of the game Risk. The advantage of being a new strategy game is that at this point in time there is not a wealth of information on opening theory, endgame play etc. - it is that most exciting time in a game's development.

Shacru is a simple and relatively light game that takes less than two minutes to learn. It is a strategy game where you have to watch what your opponent(s) are up to. Chevrons can only move one space at a time, and each time they move they place a marker on the square moved to. A coloured marker that does not belong to you is a barrier, so each player is effectively trying to build walls which their opponents cannot pass through, so that at the end of the game they can keep gaining territory in order to have the most at the end of the game. Scores for the amount of territory won in each game by each player can be totalled across a series of games, just like tricks in a game of cards.

Shacru is a simple and relatively light game that takes less than two minutes to learn. It is a strategy game where you have to watch what your opponent(s) are up to. Chevrons can only move one space at a time, and each time they move they place a marker on the square moved to. A coloured marker that does not belong to you is a barrier, so each player is effectively trying to build walls which their opponents cannot pass through, so that at the end of the game they can keep gaining territory in order to have the most at the end of the game. Scores for the amount of territory won in each game by each player can be totalled across a series of games, just like tricks in a game of cards.

Azacru can be seen as a natural development from Shacru, though the play is so different it is misleading to call it a variation. In Azacru you are working towards making one, or a series of, connection changes as the game progresses. If you make a connection change where in addition to placing your own markers, you are removing another player's marker(s) from the board, then your chevron exits the board as soon as the move is made. This can be a good move to make for the last rounds of Azacru are usually the most crucial, and as as soon as one player says "I cannot move" on their turn, the others have just one move each left to make in which to increase the number of their markers on the board, and ideally decrease those of their opponents at the same time.

Azacru can be seen as a natural development from Shacru, though the play is so different it is misleading to call it a variation. In Azacru you are working towards making one, or a series of, connection changes as the game progresses. If you make a connection change where in addition to placing your own markers, you are removing another player's marker(s) from the board, then your chevron exits the board as soon as the move is made. This can be a good move to make for the last rounds of Azacru are usually the most crucial, and as as soon as one player says "I cannot move" on their turn, the others have just one move each left to make in which to increase the number of their markers on the board, and ideally decrease those of their opponents at the same time.